Departmental Colloquium 2019–2020: Epigraphic Habits: Ancient Epigraphy and Ancient Identity

Benedict Anderson suggested that modern nationalism depends upon widely disseminated material printed in a common language (1983). The public sphere, he maintained, relied upon print readers. In the modern world, the development of the printing press and the subsequent market for vernacular books and print publications created and reinforced discourse within language communities.

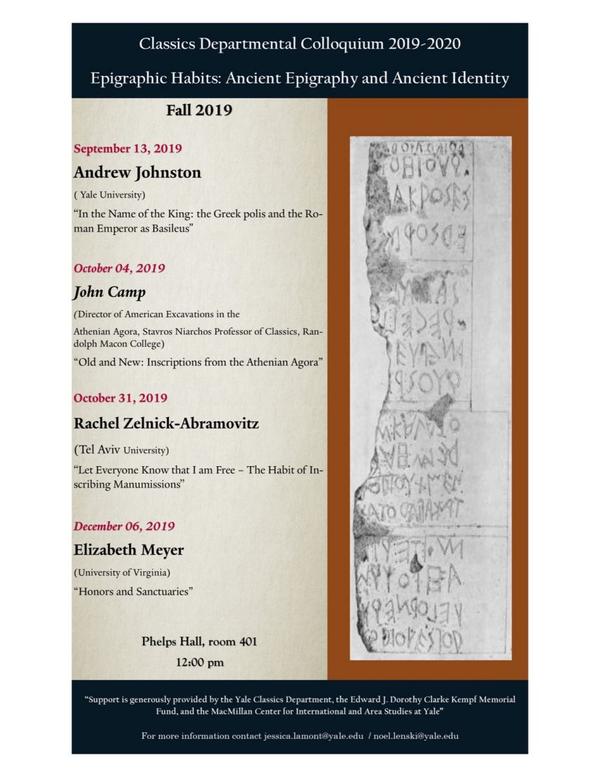

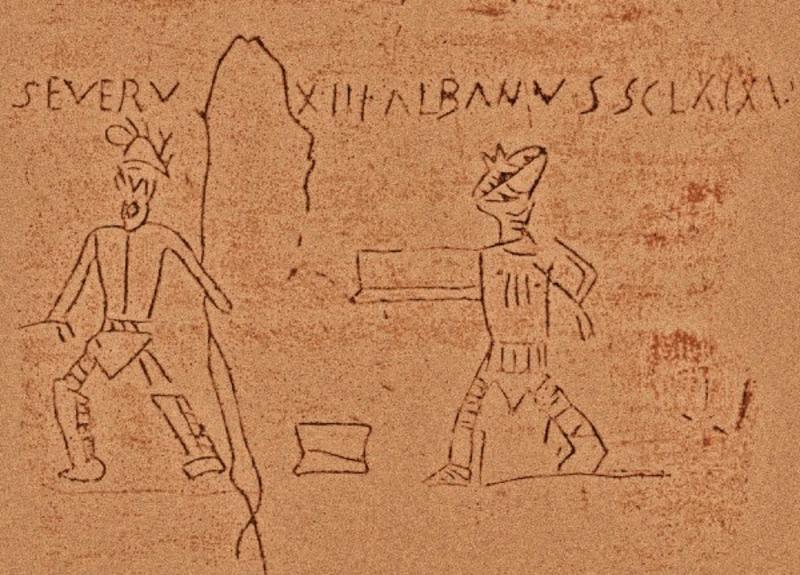

In most ancient Greek and Roman communities, the public sphere was also dappled with the written word — from public inscriptions on stone, metal, and wood, to papyrus documents, to painted and incised graffiti. Even loaves of bread and terracotta roof tiles were stamped with words and letters that carried messages with meaning. Latin and Greek inscriptions survive in the hundreds of thousands from as far east as modern Afghanistan, as far west as the British Isles and Morocco, and as far south as the mouth of the Red Sea. All of these texts were constitutive of identity, which operated on the political, literary, and — one could argue — national level. The practice of inscribing texts was itself historically determined, an idea first crystalized by Yale’s Ramsay MacMullen in a famous article on “The Epigraphic Habit in the Roman Empire” American Journal of Philology 103 (1982) 233-46. The creation of civic and imperial public inscriptions continues uninterrupted from the sixth-century BCE to the sixth-century CE. So too, do private texts, which stretch across time and space and provide invaluable information for ancient literary and social practices that constitute communities — from the commercial lead letters of Emporion (Spain) and Olbia (Black Sea), to the postcard-sized wooden tablets unearthed at the fort of Vindolanda (Britain), to the verse inscriptions of dedications found all across the greater Mediterranean. Inscribed and written texts were at the heart of ancient political, economic, social, religious, and literary communities.

“Epigraphic Habits: Ancient Epigraphy and Ancient Identity,” seeks to explore current trends and new approaches in the field of ancient history, religion, and literature through the lens of the inscribed text. The lineup of speakers will traverse a broad geographic and chronological scope, from Archaic Greece to Punic North Africa, to Roman Republic and ultimately Late Antiquity. Moreover, the speakers to be recruited specialize in literary and not just documentary texts; detailed analyses of old texts and presentations of newly discovered documents will be included, as will theoretically informed discussions of dossiers of inscriptions.

Fall 2019

September 13: Andrew Johnston (Yale University) – In the Name of the King: the Greek polis and the Roman Emperor as Basileus

October 4: John Camp (Director of American Excavations in the Athenian Agora, Stavros Niarchos Professor of Classics, Randolph Macon College) –

October 31: Rachel Zelnick-Abramovitz (Tel Aviv University) – Let Everyone Know that I am Free – The Habit of Inscribing Manumissions

December 6: Elizabeth Meyer (University of Virginia) - Honors and Sanctuaries

Spring 2020

February 7: Nazim Serbest (Yale University) –

The remaining lectures are postponed until 2020-21.

March 6: Gianfranco Agosti (La Sapienza, Università di Roma) –

April 24: Rebecca Benefiel (Washington and Lee) – Writing throughout the Roman city: Writers and audiences of ancient graffiti

May 1: Nikolaos Papazarkadas (University of California, Berkeley / Oxford University) –